Find Voice Over Artists

Gaelic Scottish Voice Over Agency

Find out why we're the most talked about Gaelic Scottish voice over agency in the UK

Why choose us?

You deserve the best! Leave your project to the experts at GoLocalise so that you can relax and be assured of getting top-notch results. Every single detail will be analysed, studied and looked after so that you do not need to worry. Some would say it’s not too classy to blow our own trumpet… but we just like to point out two very important details.

We have achieved ISO 9001 Quality Management certification in recognition of our consistent performance and high standards, and ISO 14001 Environmental Management because we care about our planet! And if you are still curious and want to know more about us, why not have a look at our studio page.

Learn more about our Voice Over Services

Let's get started!

Working alongside translation & production companies

Having a strong audiovisual department on your side makes all the difference!

With GoLocalise you get an experienced and motivated team of professionals that work regularly alongside translation and production companies. We understand the technical requirements necessary to produce perfect foreign language and English voice overs. Our project managers will assist you along the way and we’ll break down the process and present it to you without the big words or technical industry jargon, so you don’t need to worry about the technical aspects and can simply concentrate on growing your business. By working with GoLocalise you’ll be able to offer additional services, i.e., voice over, subtitling and translation to your clients, with a partner who will deliver and on whom you can truly rely.

When working with translation companies we provide easy-to-follow guidelines so that you can provide your own translations for us to “convert” into subtitles, or voice over your translated scripts. Or if you prefer, we can take the entire project off your hands and keep things simple for you – it’ your call! We’re equally used to working with production companies, so we can deliver your translations or subtitles in any language and format of your choice – either burning-in the subtitles onto the video for you, or supplying you with XML or PNG files for you to do yourself – Adobe After Effects and Final Cut Pro ready files.

Reach your target market

Don’t leave your important communication to chance. Make sure your message is clearly understood by

your audience and choose GoLocalise for your next voice over project.

We have thousands of passionate and professional voice over artists ready to work with you. No matter the type of voice you are looking for, we’ll either have it in our books or find it and source it for you. We’ll organise a casting and ensure you get the perfect voice to suit your needs.

You will also benefit from having your own dedicated project manager – a single point of contact – to guide you through your project, answer any questions you may have and make things a whole lot easier.

Meet your dedicated project manager

Your project will be in the safe hands of one of our multilingual project managers.

They will guide you through every step and ensure you understand the process. Our industry has a tendency to use lots of technical jargon but your dedicated project manager will be on-hand to untangle the mess and explain all you need to know to ensure you only pay for what you need.

If you need help in choosing the right voice over talent to deliver your message then just ask your project manager. From booking our voice over recording studios to ensuring you project is delivered on time in your chosen media, relax and let your experienced project manager take care of everything. You will receive unparalleled attention to detail and customer focus at competitive prices. You’ll wish everything was as easy as a GoLocalise voice over!

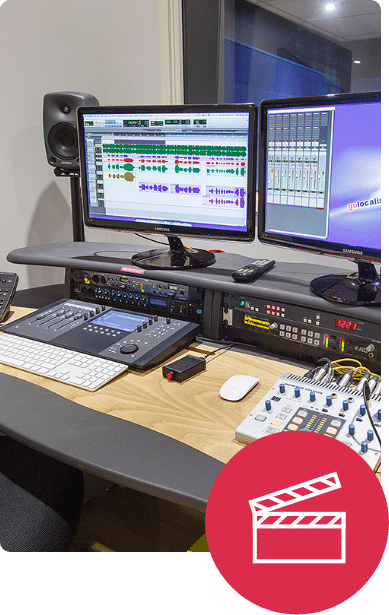

Perfect voice over recording studios

Your most discerning customers will thank you for choosing our modern state-of-the-art recording studios. Every detail has been carefully thought through for your comfort, leaving you to simply focus on what matters most – the voice over session.

Your recordings will sound beautiful and crystal clear thanks to our high-end studio sound-proofing and audio equipment, i.e. ProTools HD and Neumann microphones.

Maximise your budget by reducing the need for retakes with the help of our experienced in-house sound engineers who will professionally capture and edit your audio. And for those recordings in languages which neither you nor your client speak, we’ll bring a qualified pro to your session to add that essential ingredient. To make you feel right at home, we provide high-speed Wi-Fi Internet and air-con is available. And last but not least, we have the biggest cookie jar you’ve ever seen, that’ll make your custom brew taste even sweeter!

Types of Voice Over Recordings

Dubbing & Lip Sync Voice Over

Corporate & Presentations Voice Over

Promo Voice Over

E-Learning Voice Over

Educational Voice Over

On-hold Messages (IVR) Voice Over

Character & Video Game Voice Over

Dubbing & Lip Sync Voice Over

Want to work with the best? Our dubbing and lip sync services are trusted by leading production companies, marketing and advertising agencies and TV stations from around the world.

We work in English and foreign languages, covering all international markets.

With the wide range of on-demand and online TV channels, we can help take your show, TV series or programme global with the simple addition of an English dialogue track!

Our London dubbing studios offer a full service in script translation and adaptation, casting of the voices, recording and final audio mixing of the shows so that they are ready for broadcast.

Corporate & Presentations Voice Over

Are you looking for a voice over for your corporate video or presentation?

Then you’ve found the right place. At GoLocalise we are committed to ensuring our clients have the right tone to represent their company, service or product and we will work with you to present your message in the best possible way, so that you can impress your clients and prospects.

Once the video has been shot and edited, it’s paramount that the accompanying voice over comes across as knowledgeable about the brand and excited about the company and the services they offer. A bad voice over can make a video fall flat and impact your company’s brand and image.

Promo Voice Over

Promos are a great way to launch a product or service, kick-start a campaign, make a big announcement or to just let people know about your company.

Having a great video is important, but having an engaging voice helps hammer home your message and grab the viewer’s attention.

From deep sexy voices to the “guy-next-door”, no matter what type of promo voice talent you are after, we have what you’re looking for. We are only a call or email away or, if you prefer, visit our get-a-quote page to discuss your project in detail. You can rest assured we’ll find the right promo voice over talent for your project and needs.

E-Learning Voice Over

GoLocalise is able to provide your company with e-learning translation, localisation and voice over services, leaving you with a ready-to-host product.

You’ll benefit from an expert pool of highly-skilled linguists who have extensive experience in e-learning and a sound understanding of the particular industry sector in which you are dealing.

Our service includes the management of the entire process and delivery of content adapted to foreign markets.

The steps and services involved in any end-to-end e-learning project are: the translation of the course and on-screen text; the localisation of the course graphics; the voice over recording of the course with your preferred voice over talents; and quality control during which the localised course files are reviewed against the original files.

E-learning voice overs can be used for many applications such as training courses, step-by-step instructional and safety videos, technical information, online tutorials and many other informational and educational programmes. Whatever the application, our professional voice over talents can provide you with a clear, concise and accurate narration.

If you need a voice over to narrate your e-learning course or educational product you’ll need someone with the experience, clear diction and stamina to record large volumes of text.

Educational Voice Over

Do you remember when you first started learning a foreign language?

The educational field has seen a transformation in recent years with the introduction of new technologies like smart boards and tablet apps. This transformation is especially evident in the voice over industry.

But we can all agree that the basics are still the same – a clear voice with good diction, a neutral accent, and a slow pace for better comprehension.

And while getting the right voice over talent may seem easy… we can assure you it is not. Many factors must be considered, for example, complicated words, “tongue twister” phrases, over-articulation, contractions, and lazy mouth to name a few.

Don’t leave it to chance, make sure your content is clearly understood by your audience and choose GoLocalise for your next educational voice over project. We have thousands of passionate and professional voice over artists ready to work with you in English or any foreign language.

On-hold Messages (IVR) Voice Over

How many times have you heard a horrible voice while on hold on the phone and felt like you just wanted to hang up?

Did you know that 90% of callers placed on hold, listening to silence, hang up within 40 seconds, and 30% of them never call back?

On-hold messaging or messages on hold is a service used by businesses and organisations of all sizes to deliver targeted information to their callers while they wait on hold or while they are being transferred.

Improve your customer experience, and choose a confident voice with tons of charm, warmth and enthusiasm to properly represent your company. We work with a great variety of companies, translating, adapting, casting the voice over talents and recording the telephone prompts.

Telephone prompts are recorded, cleaned, edited, split and labelled and delivered in the format of your choice, so you do not need to worry about anything!

Character & Video Game Voice Over

Video games are not just for entertainment, but they are also used to educate users of all ages while forming strong virtual communities.

We know that the game doesn’t only have to look good and play smoothly, but also has to sound and read just right. That’s why we at GoLocalise provide all our clients with carefully selected linguists, who are not only specialists in the video game field but are also gamers themselves.

We look after every single detail when localising games into foreign languages and always use the latest glossaries for all the current video game platforms, Wii, PlayStation, Xbox, etc. so that terminology and platform word choices are always spot-on.

You’ll benefit from working with a company that provides the whole package under one roof: translation, quality control, testing and voice over services for all types of video games. The voice over process is overseen by language directors, i.e., native speakers who ensure the correct delivery, pronunciation and intonation of the script.

By using the right voices you can keep frustrated players motivated!

Learn more about Voice Over Services

Let's get started!

Gaelic Scottish

Voice Over Case Study

There is no case study for this voice over, please check again soon.

View More

Voice Over

Case Studies

Price Match Promise

Challenge Our Prices, Enjoy Our Quality

A Brief History Of Gaelic Scottish

Scottish Gaelic, sometimes also referred to as Gaelic, is a Celtic language native toScotland. A member of the Goidelic branch of the Celtic languages, Scottish Gaelic, like Modern Irish and Manx, developed out of Middle Irish, and thus is ultimately descended from Old Irish.

The 2011 census of Scotland showed that a total of 57,375 people (1.1% of the Scottish population aged over three years old) in Scotland could speak Gaelic at that time, with the Outer Hebrides being the main stronghold of the language. The census results indicate a decline of 1,275 Gaelic speakers from 2001. A total of 87,056 people in 2011 reported having some facility with Gaelic compared to 93,282 people in 2001, a decline of 6,226.Despite this decline, revival efforts exist and the number of speakers of the language under age 20 has increased.

Scottish Gaelic is not an official language of the European Union or the United Kingdom. However, it is classed as anIndigenous language under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, which the British government has ratified, and the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005 established a language development body, Bòrd na Gàidhlig, “with a view to securing the status of the Gaelic language as an official language of Scotland.

Outside Scotland, a dialect known as Canadian Gaelic is spoken in parts of Eastern Canada. In 2011, there were approximately 1,500 Gaelic-speakers in Canada with the vast majority in the province of Nova Scotia. About 350 Canadians in 2011 claimed Gaelic as their “mother tongue”.

Aside from “Scottish Gaelic”, the language may also be referred to simply as “Gaelic”. In Scotland, the word “Gaelic” in reference to Scottish Gaelic specifically is pronounced [ˈɡalɪk], while outside Scotland it is often pronounced /ˈɡeɪlɨk/. Outside Ireland and Great Britain, “Gaelic” may refer to the Irish language.

Scottish Gaelic should not be confused with Scots, the English-derivedlanguage varieties which had come to be spoken in most of theLowlands of Scotland by the early modern era. Prior to the 15th century, these dialects were known as Inglis (“English”) by its own speakers, with Gaelic being called Scottis (“Scottish”). From the late 15th century, however, it became increasingly common for such speakers to refer to Scottish Gaelic as Erse (“Irish”) and the Lowland vernacular as Scottis. Today, Scottish Gaelic is recognised as a separate language from Irish, so the word Erse in reference to Scottish Gaelic is no longer used.

Many historians mark the reign of King Malcom Canmore (Malcolm III) as the beginning of Gaelic’s eclipse in Scotland. In either 1068 or 1070, the king married the exiled Princess Margaret of Wessex. This future Saint Margaret of Scotland was a member of the royal House of Wessex which had occupied the English throne from its founding until the Norman Conquest. Margaret was thoroughly Anglo-Saxon and is often credited (or blamed) for taking the first significant steps in anglicizing the Scottish court. She spoke no Gaelic, gave her children Anglo-Saxon rather than Gaelic names, and brought many English bishops, priests, and monastics to Scotland. Her family also served as a conduit for the entry of English nobles into Scotland. When both Malcolm and Margaret died just days apart in 1093, the Gaelic aristocracy rejected their anglicized sons and instead backed Malcolm’s brother Donald as the next King of Scots. Known as Donald Bàn (“the Fair”), the new king had lived 17 years in Ireland as a young man and his power base as an adult was in the thoroughly Gaelic west of Scotland. Upon Donald’s ascension to the throne, in the words of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, “the Scots drove out all the English who had been with King Malcolm”. Malcolm’s sons fled to the English court, but in 1097 returned with an Anglo-Norman army backing them. Donald was overthrown, blinded, and imprisoned for the remaining two years of his life. Because of the strong English ties of Malcolm’s sons Edgar, Alexander, and David – each of whom became king in turn – Donald Bàn is sometimes called the ‘last Celtic King of Scotland’. He was last Scottish monarch to be buried on Iona, the one-time center of the Scottish Gaelic Church and the traditional burial place of the Gaelic Kings of Dàl Riada and the Kingdom of Alba.

During the reigns of the sons of Malcolm Canmore (1097-1153), Anglo-Norman names and practices spread throughout Scotland south of the Forth-Clyde line and along the northeastern coastal plain as far north as Moray. Norman French became dominant among the new feudal aristocracy, especially in southern Scotland, and completely displaced Gaelic at court. The establishment of royal burghs throughout the same area, particularly under David I, attracted large numbers of foreigners speaking ‘Inglis’, the language of the merchant class. This was the beginning of Gaelic’s status as a predominantly rural language in Scotland. The country experienced significant population growth in the 1100s and 1200s in the expanding burghs and their nearby agricultural districts. These economic developments surely helped spread English as well.

Gaelic still retained some of its old prestige in medieval Scotland. At the coronation of King Alexander III in 1249, a traditional seanchaidh or story-teller recited the king’s full genealogy in Gaelic all the way back toFergus Mòr, the mythical progenitor of the Scots in Dál Riata, “in accordance with the custom which had grown up in the kingdom from antiquity right up to that time”. Clan chiefs in the northern and western parts of Scotland continued to support Gaelic bards who remained a central feature of court life there. The semi-independent Lordship of the Isles in the Hebrides and western coastal mainland remained thoroughly Gaelic since the language’s recovery there in the 12th century, providing a political foundation for cultural prestige down to the end of the 15th century.

That being said, it seems clear that Gaelic had ceased to be the language of Scotland by 1400 at the latest. It disappeared from the central lowlands by c1350 and from the eastern coastal lowlands north of the Mounth not long afterwards. By the mid-1300s English in its Scottish form – what eventually came to be called Scots—emerged as the official language of government and law. Scotland’s emergent nationalism in the era following the conclusion of the Wars of Scottish Independence was organized using Scots as well. For example, the nation’s great patriotic literature including John Barbour’s The Brus (1375) and Blind Harry’s The Wallace(bef. 1488) was written in Scots, not Gaelic. It was around this time that the very name of Gaelic began to change. Down through the 14th century, Gaelic was referred to in English as ‘Scottis’, i.e. the language of the Scots. By the end of the 15th century, however, the Scottish dialect of Northern English had absorbed that designation. English/Scots speakers referred to Gaelic instead as ‘Yrisch’ or ‘Erse’, i.e. Irish. King James IV(d. 1513) thought Gaelic important enough to learn and speak. However, he was the last Scottish monarch to do so.

What our happy customers say

I really enjoy working with GoLocalise. The team is very nice and flexible, and they deliver subtitles of high quality, both from a technical and linguistic point of view. Subtitling is a stress-free matter when it is in their hands, I would definitely recommend their services.

Marion Hirst

Translation Project Manager at Language Wire

I really love working with GoLocalise. Their subtitling department takes care of everything and they always deliver the best quality files. I’m also very happy that they’re willing, and capable, to work with all kinds of requests, and are always happy to help me and make the process better. The team is also so very helpful, and very nice to work with. I always recommend their services to everybody.

Patricia Leon-Fedorko

Account Specialist at Advanced Language

We have used GoLocalise on a regular basis for projects in a number of languages. The service we receive is great. The team is always friendly and professional. The voiceovers we receive are of a very high quality and the turnaround is extremely quick. We are very happy to recommend GoLocalise to other businesses.

Jo Samuel

Animator at Pixel Circus

GoLocalise has been Atlas’s sole provider of translation and foreign voiceover services since 2011. Their friendly and efficient team have localised a range of technical and behavioural projects and in a variety of multimedia formats. Atlas considers GoLocalise to be our localisation partner; trusted to consistently deliver on time and to a high standard.

Thomas Kennedy

Designer at Atlas Knowledge

In my third year at drama school I recorded a demo at GoLocalise and it was the best thing I could have done before entering the industry. I highly recommend actors to use their studio and services to record a demo. Since recording, I have booked for a paid VO job too! Not only are they professional, provide a great service and produce top quality work; the whole team are wonderful and make you feel very welcome. 100% recommend!!!

Nicola

English UK Voice Over Talent

GoLocalise are a joy to work with. Nothing is too much trouble for them and we always appreciate their good advice, flexibility, fairness and professionalism. I would highly recommend them for any project.

Stefanie Smith

Producer at Education First

The Complete Solution To Adapt Your Content

Looking to get your entire project under one roof? Look no further, we can help you make life easier for you!

- Neumann Microphones

- On-hand Sound Engineers

- Talented Voice Over Actors

- State-of-the-art Recording Studios

- Tailored to Your Business

- Laser-Focused Project Managers

- Global Network of 600+ Languages

- Stringent Quality Control Processes

- Professional Subtitlers

- Open/Closed Captions & Web

- Industry-Standard Software

- Subtitle Burn-in & Graphic Editing

- Improve accessibility

- Reach a wider audience

- Increased SEO and video views

- Maximise your video's engagement